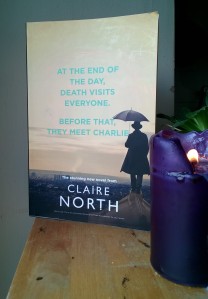

First of all, happy holidays and new year to all of you! I’m reading something new for the new year. I got this copy of Claire North‘s The End of the Day (Orbit, April 2017) from work, our fiction buyer handing it to me and saying “can you read this for me please?”. I was sceptical, usually the proofs that get fobbed off on me (with some notable exceptions) aren’t that great (simply by the rules of trickle-down economics, I usually receive the dregs). I’m happy to say that this book is another exception to that rule.  There’s a kind of divination, known as Fal Gush, that (to put it rather simply) involves standing on a street corner or behind a fence and gleaning information about the future by interpreting the words of passersby, dropped randomly from the proverbial eaves. North, in The End of the Day, brings to mind this practice; she lends prophetic-or at least ominous-significance to a series of disembodied quotes sprinkled throughout the narrative. These give new meaning to the thread of the narrative, to the actions and words-said and unsaid-of the characters.

There’s a kind of divination, known as Fal Gush, that (to put it rather simply) involves standing on a street corner or behind a fence and gleaning information about the future by interpreting the words of passersby, dropped randomly from the proverbial eaves. North, in The End of the Day, brings to mind this practice; she lends prophetic-or at least ominous-significance to a series of disembodied quotes sprinkled throughout the narrative. These give new meaning to the thread of the narrative, to the actions and words-said and unsaid-of the characters.

Dialogue is, I think, one of North’s strongest suits: her characters speak in halting, broken sentences that sound like the words of real people (though as an American I found bits of the US chapters a bit caricaturish), not cardboard cutouts or automatic plot engines. It’s clear that North is someone who actually listens to people when they speak, a quality which I-as a linguist and a writer-find admirable. North’s style of writing is as naturalistic and organic as it is artful, so much so that her characters tend to wax as poetic as her prose. I can forgive this of Carlie, the protagonist, a man whose sincerity and isolation makes his long-winded speeches to the dying (and the living, to the other harbingers, his girlfriend, his friends and foes, pretty much to any other character in the book) believable and endearing. But there are a few times when the other characters seem to be struck with a kind of divine influence, rendering them implausibly poetic, in essence turning them into mouthpieces for a narrator whose political agenda becomes increasingly clear as the book progresses.

Hwy59 by M&R Glasgow

This clarity of agenda, conveyed in the talking points enumerated in the sound bite chapters, and indeed even in the content of the narrative-the final death of a culture and language, the escape of a pair of lesbians from a country whose laws make their very existence illegal, a trek across a melting ice cap-that pulled me out of the story at times. I believe (as do I think many writers) that literature should challenge the status quo, be an agent of social change. But I also believe that the ego of the writer means the death of the story; the power of literature to enact social change is rooted in its ability to change the reader’s mind without them realizing. Build a believable world, set out a problem representative of something in the world you wish (often unconsciously) to change, and the reader will come to their own conclusion.

North builds a believable world: one of the triumphs of this book is the way North gives texture to the speculative elements of the book: the system of Harbingers, their personalities, the way different people perceive Death and the other Riders. North grounds the ineffable in the banal (Death’s office is in Milton Keynes, the Harbinger had to interview for the job, etc.), rendering existential questions everyday and often irreverently funny. But her approach-in my opinion, anyway-is a little lacking in subtlety. The sound bite chapters, quotes from straw-man fictional people often (especially in fictional America) demonstrating profound ignorance, toe the line between storytelling and preaching.

In the end it is North’s sincerity that saves this book: her characters-especially the women-are developed and likeable, vulnerable without being victims. She takes as much care rendering nonwestern people and places as she does western, indeed, in many ways the chapters set in Lagos, Syria, Oounavik are the most powerful, and convey the meat of the story, carrying the narrative and contributing the most to the development of Charlie’s character.

Overall, The End of the Day is a sincere, topical, humane piece of writing, and though it has a political agenda that at times threatens to eclipse the power of its own narrative, it’s also thoughtful, inventive and irreverent, perfect for fans of Terry Pratchett or Netflix/Channel 4’s Black Mirror. The book is available for pre-order here, or at your local bookstore.

Hubbard Glacier Calving by Kyle West